Strong Foundations

Misplaced Icons – Nigeria’s Lost Stars (Part One) Thunder

February 25, 2021

Nigeria’s Trailblazers

February 25, 2021Strong Foundations

By Satish Sekar © Satish Sekar (February 24th 2021)

The Architect

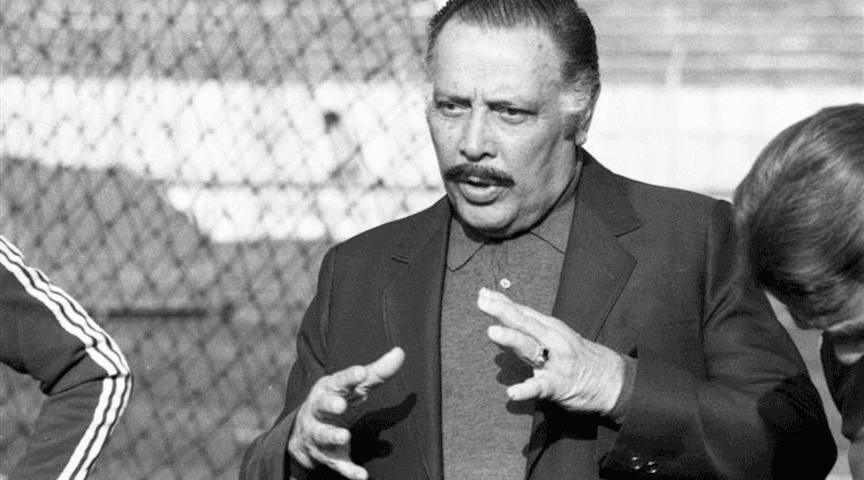

He taught the players and converted some like Odegbami to a position where he would influence the game more – in Odegbami’s case from striker to winger. Otto Glória was fortunate to inherit excellent foundations laid by Tihomir ‘Tiko’ Jelisavčić. The Yugoslav-born former player coached Nigeria from 1974-78.

Unfortunately, Nigeria failed to qualify for the World Cup in 1978 and the Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) defeat to Uganda in the semi-final signalled the end for Jelisavčić. However, he had laid the foundations, and is held in very high esteem by Odegbami who refers to his former coach as ‘Father Tiko.’

Jelisavčić died in a car crash in México in June 1986. In 1980 his successor, the Brasilian, Otto Glória led Nigeria to their first AFCON title by building on the foundations built by Jelisavčić. Glória took Nigeria to South America to learn the Brasilian way. By the time they returned, they had completed the task of abandoning the British model of football begun by Jelisavčić. They were playing more attractive football and they were more successful too.

A Learning Curve

Prior to independence in 1960 Nigeria began its rivalry with west-African neighbours Ghana. There’s no doubt that in the early stages of the rivalry Ghana was on top. Ghana’s Black Stars could even afford political interference of the worst kind – the 1966 coup at first. The roots of Dr Kwame Nkrumah’s Football Revolution ere so strong that even after it the Black Stars reached two AFCON finals – their surprise defeat in the 1968 final was a self-inflicted wound. But Nigeria had its own political crisis – Biafra – and that affected its progress in football.

Nigeria took a decade to begin to progress after their first appearance in the AFCON Finals (1963). They took their beatings – Sudan and the United Arab Republic (UAR), which was a short-lived union of Egypt and Syria – losing 4-0 and 6-3. It was a hard lesson that took years to learn.

It wasn’t until 1974 that Nigeria began to develop. Father Tiko took over the Nigerian team. Two years later he steered them to third place – progress. The same result in 1978 was considered a failure too many. Ghana’s success for the third time allowed the Black Stars to keep the trophy outright – the first time any African nation had been allowed to do so.

That, combined with Nigeria’s defeat in the semi-final to Uganda, spelled the end for Jelisavčić.

Credit

Although Otto Glória broke Nigeria’s duck at AFCON and will always be credited for that – he deserves a large slice as he brought innovative football ideas to Nigeria and helped to implement those ideas – it became part of the Super Eagles’ DNA, he had strong foundations to build on.

Jelisavčić played a part – a large one – in shaping Nigeria’s football identity. Breaking with the English way of playing was important. Odegbami waxes lyrical about Glória and how he brought Brasilian football to Nigeria by bringing Nigeria to Brasil, he acknowledges the role of Jelisavčić in giving the Brasilian a sound base to build on. The late Yugoslav deserves recognition and appreciation for facilitating Nigeria’s success